The Kelp Highway: How the Pomo People Reached the Mendocino Coast

The story of how humans first arrived on the Mendocino Coast begins not with footprints across an ice bridge, but with a journey along a ribbon of kelp forests stretching thousands of miles down the Pacific coastline.

The kelp highway theory proposes that the ancestors of the Pomo people traveled southward from Beringia between 15,000 and 10,000 BCE, following nutrient rich kelp ecosystems that provided continuous marine resources for coastal migration.

This revolutionary understanding of ancient settlements challenges earlier models that focused exclusively on inland routes, revealing instead a sophisticated maritime culture that recognized the ocean not as a barrier but as a highway of abundance.

By 10,000 BCE, Pomo peoples had established permanent communities along what is now the Mendocino Coast, beginning a continuous cultural presence spanning over 12,000 years and making this region home to one of North America's longest documented indigenous histories.

Following the Kelp Forest Highway

The kelp highway theory emerged in the early 2000s as archaeologists and marine biologists recognized that giant kelp forests (Macrocystis pyrifera) created a continuous coastal ecosystem from Japan through Beringia and down to Baja California during the late Pleistocene era.

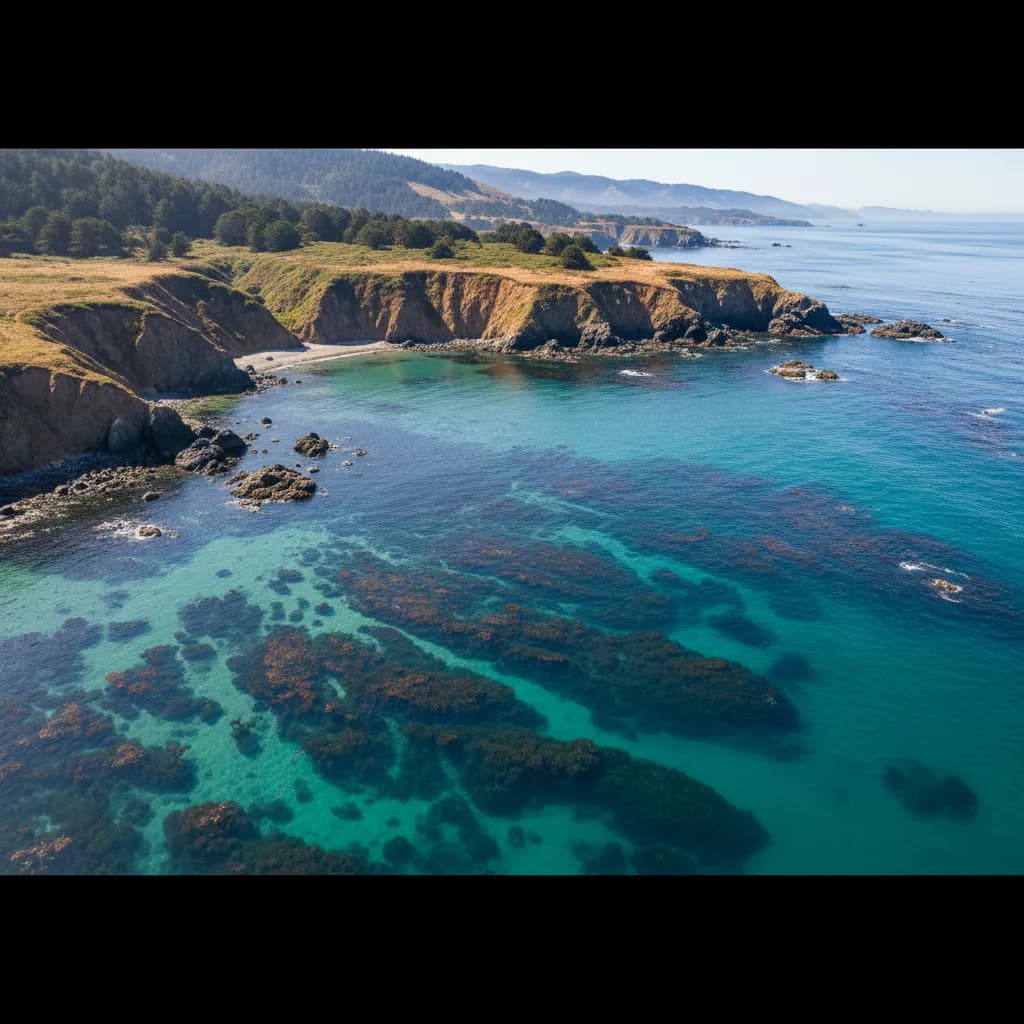

These underwater forests, visible as dark ribbons from shore and extending up to 150 feet toward the surface, supported dense concentrations of fish, seals, sea otters, shellfish, and seabirds.

For early maritime peoples with watercraft and coastal knowledge, kelp forests functioned as both navigation markers and floating supermarkets.

Unlike the interior ice free corridor, which remained blocked by glaciers until approximately 12,500 BCE and offered limited resources, the kelp highway provided year round access to protein rich foods.

Mussels, abalone, sea urchins, and rockfish thrived in kelp holdfast communities.

Seals hauled out on nearby rocks.

Migrating whales followed the kelp line.

Early peoples traveling this route could move southward while maintaining familiar subsistence patterns, never venturing far from reliable food sources.

Archaeological evidence supporting coastal migration includes the Arlington Springs Man, discovered on California's Channel Islands and dated to approximately 13,000 years ago, proving that sophisticated maritime cultures existed along the California coast far earlier than previously believed.

The presence of obsidian tools on Channel Islands sites, sourced from mainland quarries, demonstrates that these early peoples possessed watercraft capable of crossing ocean channels.

Similar patterns of early coastal occupation appear at sites throughout the Pacific Northwest and California, with dates consistently pushing back the timeline of human arrival.

The Pomo people's deep knowledge of kelp and marine resources likely represents cultural continuity stretching back to these original kelp highway migrations.

Traditional Pomo practices included harvesting bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) for fishing line, using its hollow stipes as containers, and gathering the abundant shellfish and fish that kelp forests supported.

This wasn't merely subsistence gathering but rather sophisticated resource management developed over millennia.

Pomo Settlement and Cultural Flourishing

By 10,000 BCE, Pomo peoples had established permanent settlements throughout the Mendocino Coast region, developing 72 distinct communities that shared linguistic and cultural connections while adapting to local environments.

These weren't simple hunter gatherer camps but complex societies with sophisticated social structures, extensive trade networks, and artistic traditions that would become renowned worldwide.

The indigenous history of the Mendocino Coast centers on this remarkable cultural achievement.

Pomo communities developed expert knowledge of seasonal resource cycles, knowing precisely when salmon would run in coastal streams, when mussels reached peak abundance, when acorns matured in coastal oak groves, and when seaweed could be harvested from intertidal zones.

This ecological literacy, passed through generations, enabled sustainable resource use that supported substantial populations for over 10,000 years without depleting the ecosystems they depended upon.

Pomo basket weaving traditions, considered among the finest in North America, reflect this deep cultural continuity.

Using sedge roots, willow shoots, bulrush, redbud, and other coastal plants, Pomo weavers created baskets so tightly woven they could hold water, decorated with patterns incorporating feathers, shells, and geometric designs that carried cultural meaning.

These weren't simply utilitarian objects but expressions of cultural identity, spiritual practice, and accumulated knowledge about plant ecology and material properties.

The coastal migration patterns established by their ancestors continued to influence Pomo culture.

Communities maintained extensive trade networks along the coast and inland, exchanging coastal resources like dried seaweed, shells used for currency, and salt for inland products including obsidian, acorns from valley oak groves, and materials from other ecological zones.

This interconnection created a regional culture that was distinctly coastal yet connected to broader networks.

Traditional Pomo territories encompassed the entire Mendocino Coast region, from the marine terraces where villages clustered near freshwater sources to the redwood forests that provided shelter and materials.

Village sites were carefully chosen for access to multiple resource zones: ocean beaches for shellfish and seaweed, rocky points for fishing, coastal streams for salmon, and nearby forests for game and plant materials.

Legacy and Contemporary Connections

The disruption of traditional Pomo territories began in the 1850s with American settlement and intensive logging operations that transformed the Mendocino Coast.

Ancient village sites were displaced, traditional resource access was restricted, and populations declined dramatically due to disease, violence, and forced relocation.

Yet Pomo cultural heritage persists through contemporary tribal communities, cultural practitioners, and ongoing efforts to preserve and revitalize traditional knowledge.

Visitors to the Mendocino Coast today walk landscapes shaped by over 10,000 years of Pomo presence.

The marine terraces that characterize the coastline contain archaeological sites documenting this long habitation.

The kelp forests visible from headlands like those at MacKerricher State Park north of Fort Bragg represent the same ecosystems that guided ancient peoples to these shores and sustained Pomo communities for millennia.

Understanding this indigenous history adds profound depth to experiencing the coast's natural beauty.

Visiting with Cultural Awareness

Several locations offer opportunities to learn about Pomo culture and the kelp highway theory while experiencing the Mendocino Coast's natural environments.

The Mendocino County Museum in Willits houses significant Pomo basket collections and provides historical context about indigenous settlement.

The Grace Hudson Museum in Ukiah features extensive Pomo cultural exhibits, including traditional baskets, tools, and photographic documentation.

MacKerricher State Park, located three miles north of Fort Bragg, provides accessible coastal access where kelp forests are visible offshore during calm conditions.

The park's coastal trail follows ancient marine terraces, and interpretive materials acknowledge the area's indigenous heritage.

Fall months from September through November offer the clearest weather for coastal viewing, with calm seas making kelp forests particularly visible through turquoise water.

After exploring coastal sites around Fort Bragg, visitors often stop at Mercato Bakery on Franklin Street for authentic Italian espresso and pastries, reflecting the town's later settlement by immigrants who, like the Pomo people's ancestors millennia before, recognized the coast's abundant resources and made it home.

The kelp highway theory reminds visitors that human history on the Mendocino Coast stretches back not centuries but millennia, and that the ocean has always been not a barrier but a pathway for peoples with the knowledge and skills to navigate it.

The Pomo people's 12,000 year presence represents one of the world's great stories of cultural continuity, environmental adaptation, and sustainable living.

Recognizing this heritage transforms a visit to the Mendocino Coast from simple tourism into an encounter with one of North America's oldest and most enduring human landscapes.

The Mendocino Coastal Chronicle documents the natural beauty, cultural heritage, and historical significance of the Mendocino Coast for visitors, students, and researchers. Our articles combine historical research, ecological science, and cultural appreciation to celebrate this unique region.

Educational Resources: For current visitor information, hours, and fees, please contact local visitor centers and state park offices. Conditions and regulations may change seasonally.

Indigenous Acknowledgment: The Mendocino Coast is the ancestral homeland of the Pomo and Yuki peoples, who have stewarded these lands for thousands of years. We honor their continuing connection to this place.

Published by the Mendocino Coastal Chronicle | Educational content for the appreciation and understanding of California's North Coast heritage.